Where Funders and CEOs each Excel

The decision was hard, and the largest funder and CEO of the project were at odds with each other. These were both exceptional professionals - the funder was modest yet highly informed, a leader in the ecosystem. The founder was a rising star in their field, with this being the second successful project they had run. In many ways, they weren't debating the specific question so much as who was better placed to make a given decision.

It would be much easier if one of these two were clearly less competent. The worst funders consistently make worse decisions on virtually everything compared to a great CEO, but the same is also true in reverse: a weak CEO can be outperformed by great decision-making from a top foundation. However, when both are outstanding or roughly equal relative to their roles, I believe certain decisions optimally can be split up based on the type of decision.

When Funders Excel

Cross-sector comparative analysis: Funders naturally have a more zoomed-out view, allowing for easier cross-comparison. Knowing what other similar actors have done and what those actions accomplished is incredibly valuable. Particularly if the funder is well-specialized, they will often have more knowledge of what price points and outcomes are being achieved by others. This gives them a natural benchmark for intuitive comparison. This tends to mean funders notice first when a plan is unrealistic or outcomes are falling significantly below expectations. Decisions that might tie to this include: "Is this charity cost-effective?", "Is missing a target due to sector-wide challenges or charity-specific issues?", and "Is this charity's work being covered by multiple actors or just them?"

Decisions with inherent bias: Everyone thinks their own baby is the cutest. It's remarkably difficult for CEOs and founders not to be biased toward their charity. They may believe mistakes were inevitable given the circumstances, while victories were mostly due to their organization rather than external factors. Funders often maintain more of an outside view; they might be supporting ten actors in the space doing similar work and don't have as much personal investment in a specific project. They aren't as personally affected by decisions, making it easier for a funder to recognize when a project might need to shrink than a founder who is deeply committed to it. Relevant decisions include: "Should the project shrink or shut down?", "Should the CEO continue to lead this project?", and "Is the spending reasonable for what is being accomplished?"

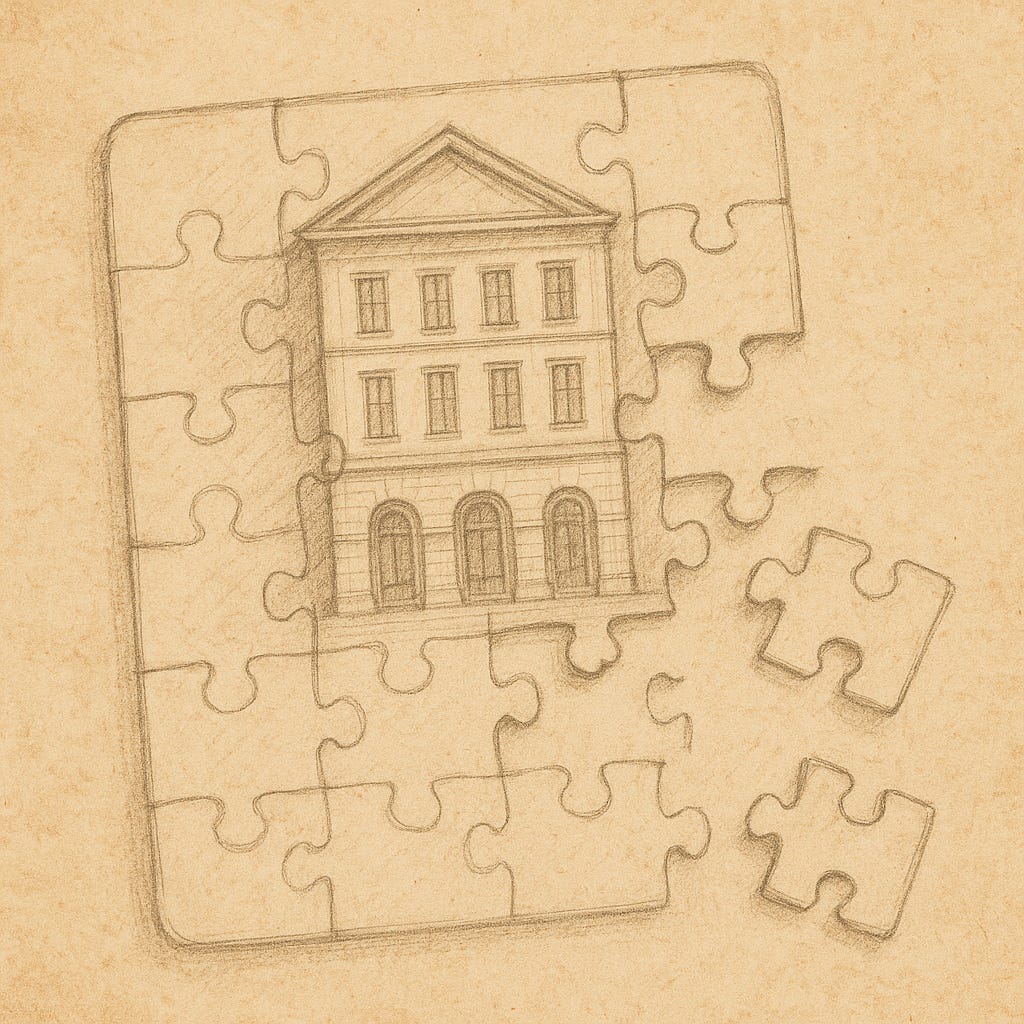

Ecosystem thinking: Charity founders sometimes focus narrowly on their specific organization's impact, but if someone is saved from malaria, it doesn't really matter whose logo appears on the intervention. Funders tend to think in ecosystem terms - what's missing across all organizations, who might step up if another actor stepped back. Ultimately, for a funder, a given NGO is one piece of a bigger puzzle. While the CEO focuses on making that piece exceptional, the funder thinks more about how it fits into the overall landscape. Related decisions include: "Does the ecosystem need more innovators or implementers?", "If you expand to an area, who steps back from that area?", and "Who is doing the best job at a given function in the ecosystem?"

When CEOs Excel

Organizational identity: Every organization needs a distinct identity - what makes it different, its focus area and mission, what cultural factors enable it to excel, and what team needs to be built. Aspects related to organizational identity fall more clearly in the CEO's domain. They are like a homeowner building their own home versus a corporate landlord managing hundreds of properties. Decisions such as "What are your values?", "What type of staff do you hire?", and "Which areas do you focus on and which do you avoid?" are best made by the CEO.

Implementation details: While the funder examines the ecosystem, the CEO makes their puzzle piece as robust as possible. Aspects of how things get done tend to be the CEO's strength - considering required team composition, establishing appropriate OKRs, and determining how resources move most effectively from point A to B. Funders ultimately aren't sufficiently detail-oriented to handle these operational elements in an informed way.

Internal trade-offs: Numerous issues involve internal trade-offs - competing priorities that must be balanced. Typically, there are too many considerations for someone not working full-time in the organization. Examples include which department receives more staffing resources or which priority gets temporarily deprioritized during uniquely busy periods. A way to frame it is the more a decision only involves NGO staff the more it falls to the CEO and the more it involves multiple NGOs it might fall more to the fund.

High time cost decisions: Ultimately most founders are putting in 40 hours a week (or more) to their specific project. A funder at best is putting in full time across a dozen projects and sometimes is putting in part time spread across hundreds. If a decision involves crunching and comparing a ton of data or doing a long research deep dive often the NGO leader will be able to do it better. When depth matters more than breadth it tends to fit the founder better than the funder.

Not all cases present clear decision ownership. Who has better insight on partnerships and collaborations, for example, likely depends significantly on who has more experience with the specific partner in question. Long-term planning ideally incorporates perspectives from both roles. I believe the best funders and CEOs recognize intrinsic systemic differences between their positions. I view it as funders bringing financial resources while CEOs bring talent, with both serving as relatively equal partners working toward shared goals. The greater the alignment between them and the more awareness each has of their respective strengths, the better the outcomes.