The argument was flawless. I had thought about it thoroughly and could not find a hole in it.

This has happened to all of us at one point or another, but I want to ask the meta question of how seriously should we take it? On the one hand, not being able to come up with a counter-argument seems like a pretty damning sign. On the other hand, it's pretty easy to modify this to take away a lot of its power.

Let's try a simple experiment:

The argument was flawless. I had thought about it thoroughly and could not find a hole in it. I had, of course, had 4 drinks that night, so the details were a bit foggy in my mind.

Hmm, all of a sudden this seems a lot less persuasive. But then it's not just that a solution could not be found, it's also about whether the person analyzing it is impaired. Clearly, if someone is drunk, their reasoning is not going to be at their peak. But of course, it's more than that. What about this situation?

The argument was flawless. I had thought about it thoroughly and could not find a hole in it. My 10-year-old self was fully convinced.

Here I am not drunk, but the situation does lead you to question what deductive power I would have at this age. The broader point is that not being able to find flaws in an argument really depends on the person struggling to find flaws. Both these first two are raw reasoning ability examples, but what about domain specificity?

The argument was flawless. I had thought about it thoroughly and could not find a hole in it. Of course, they did have a PhD in physics, and I had only taken it in high school.

Now it's not just competence; it's also domain expertise. A PhD in physics could be bold-faced lying to me, and I would not have the competence to determine if what they were saying was true or not.

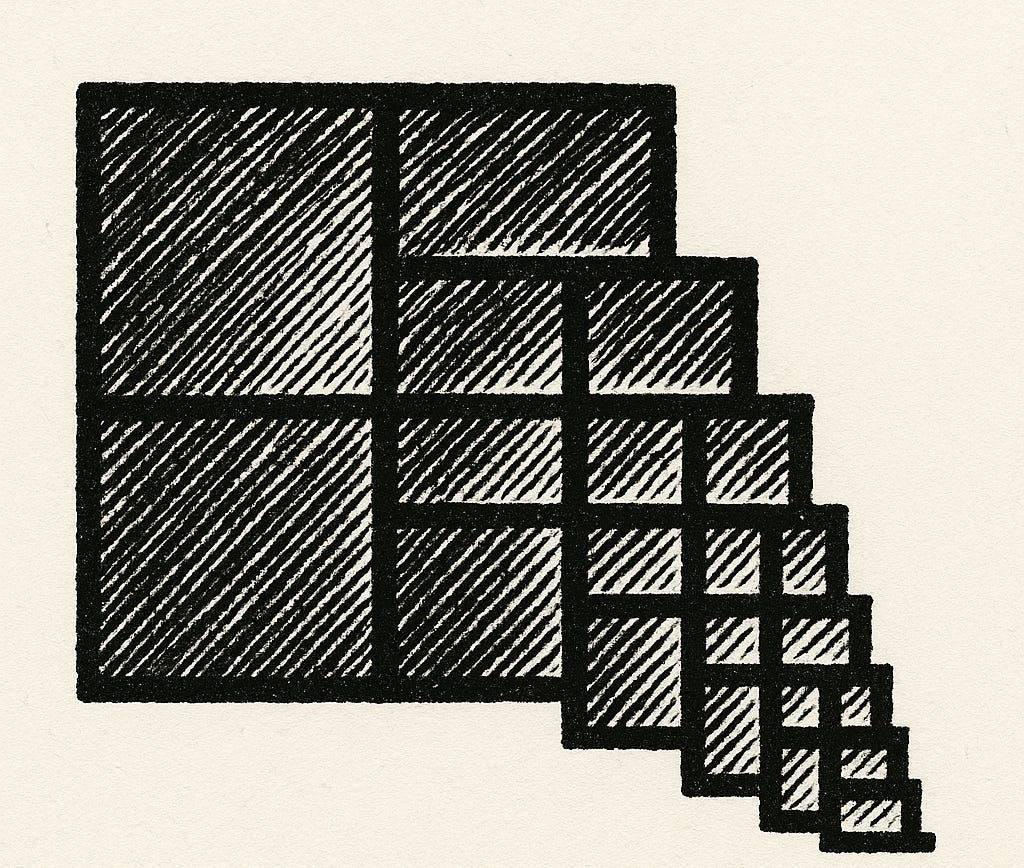

See the pattern? Our inability to find flaws depends enormously on who we are, what we know, and our mental state. Yet we make life-changing decisions based on arguments we "can't refute" every single day.

You may be saying this is all obvious—of course in some areas, not being able to reason a flaw or next step yourself might only be slight evidence of the sentiment being true based on your competence and knowledge of an area. However, this happens all the time in the real world. Have you ever read a newspaper article you found significantly changed your mind? How about a short blog post? Did you question if you would actually be informed enough in the topic to know any difference? Or if your mind was sharp when reading this article?

I once told one of my friends the most I could update from a single conversation would be to "I should read a full book on that." No single conversation could fully convince me of a topic, even if every cell in my brain was shouting it was true. This could be a sign of closed-mindedness, but I change my mind far more than most people, so I don't think that is necessarily true; it's more a modesty. I just don't trust my brain enough to find all the flaws. The evidence for this is abundant. I can look at my track record and see historically how many arguments I could not find flaws in but were later proven to have flaws (still waiting on my self-driving car).

Let me share some more concrete real-world examples:

One example I have heard multiple times is the line "I don't see any difference between carbon and silicon as a substrate or any reason why intelligence should only occur in carbon" (in reference to AI). Now at the surface level, I agree; I too cannot see any difference off the top of my head as a person ~0 informed about what the biochemical difference might be. I just don't really find that a compelling argument. In fact, it updates me ~0. My prior is that even if there were huge differences, I would not really know them, not to mention being able to know with confidence how they could affect the construction of artificial minds. Finding something intellectually persuasive should not always give it much credit, particularly if you would not be informed enough to know the difference. (P.S. They are super different if you look into it, which I did after I heard this argument a couple of times.)

Let's try another. I love the idea of guaranteed minimum income; from my cursory reading, it seems to solve many problems and create relatively few in its place. However, as a meta-principle, I give ~0 credence to this intuition. I am not an economist, and even if I was, they have radically different schools of thought. Lots of ideas that sound great fall apart in the real world, and I would not predict for myself (or most economists, really) to know the difference without real-world evidence of it working. (P.S. People are doing studies on this as we speak, and I am keen to read the results if well-conducted, as that will update me in a stronger direction.)

A fun historical one: Zeno's paradoxes was a compelling argument that was roughly if you move halfway towards something and then halfway again, you could do that indefinitely and never reach your destination, eternally getting halfway closer. This stumped philosophers and more for years, but turns out it's relatively easy to solve with calculus and set theory. An argument seeming unbeatable but that goes against reality, I tend to think, is more likely we/me have not got the methodology/ability to solve than that reality is wrong.

I think it's common for people to read solely the case for something or the case against it and more or less make up their minds based on cherry-picked information, all aimed at pitching a certain conclusion relaying on their intuition of how good the arguments are to carry a lot of weight. I think that if you are a bit more modest and assume you will probably not always be able to tell good arguments from bad ones, you take pretty different actions. You move more thoughtfully and more carefully intellectually.

I sometimes call this the "Drunk Human Hypothesis" – we're all stumbling through complex problems with impaired judgment, even when stone-cold sober. If I was drunk, I would take what I think a little less seriously, as I know I would be impaired even if I felt super confident about it. I know at a meta level that is what feeling drunk feels like. But what if I thought I was always a bit irrational, overconfident, and too likely to believe arguments I can't see flaws in?

Sadly, I think that is the world we live in, and being a little bit more modest in our sense of what human brains can realistically compare and decide on, I think, can lead to better, more sober conclusions in the long run.

The next time you can't find a hole in an argument, don't surrender your judgment. Instead, ask: "Would I even recognize the hole if it existed?" This simple question – acknowledging your own limitations – might be your best defense against persuasive nonsense and might cause you to dive a little deeper.

Scott Alexander on the same thing: https://slatestarcodex.com/2019/06/03/repost-epistemic-learned-helplessness/